[drop-cap]

We live in addlepated times. This old-fashioned word is a singularly suitable descriptor for the state of our minds within our contemporary context. Etymologically, it combines the “pate,” the site of brains or intelligence, with “addled,” a word whose meanings include muddled thinking, loss of the capacity to reason, and rotten eggs, which cannot be fertilized or hatch new life. We have, indeed, found ourselves with scrambled, rotten eggs for brains.

The world has always had its share of confusion, foolishness, insanity, and craven cruelty, and it will certainly go on in this way while human beings exist and face the choice between integrity and corruption, moral courage and complicity, seriousness and silliness. But raging confusion permeates the present moment, amplified by the digital megaphones of social media, podcasting, AI, “creatives,” “influencers,” bots, trolls, and algorithm-based digital marketing. We tap, tap, tap on our phones and screens, looking for updates, seeking responses, hoping for “likes” and “followers,” for a human voice to emerge (and sometimes imagining one) within the toxic miasma.

We are also overwhelmed by the sheer depravity of much of our public discourse. Public figures and public officials lie brazenly with intent, with abandon, and without consequences. Graft, corruption, and self-enrichment have become ordinary and are even admired as American success narratives. The inexpert and the incompetent, equipped only with virulent ideologies, have been exalted and installed in positions of power.

Pick the day and look around. You’ll see assaults on voting rights, the encroaching mobilization of the military to control public life in American communities, masked ICE agents disappearing human beings from Home Depot parking lots and city sidewalks, respect for science and education replaced by near-medieval doctrines based on lies and invalidated concepts, sycophantic pandering to an infantile and narcissistic President of the United States, burgeoning and cruel nationalism both internationally and in the USA, the breakdown of commitment to human rights and international law. There’s no point in naming the shock du jour; between the moment at which I write these words and the moment in which you read them, a flowing stream of outrageous events will have rattled the bars of our cages.

Because it does feel increasingly as if we live a caged—and therefore helpless—existence and the ubiquitous mediation of daily life is in large part responsible for both the mess in which we currently find ourselves and feelings of being hopelessly trapped. As Frank Bruni put it recently, “the digital revolution has created a chaos of boutique obsessions, splenetic social media posts, deepfakes and slop. Reality is whatever we’ve decided to purchase at the pick-your-truth bazaar.”1 And human beings, confronted with and confused by a truculent and arbitrary reality, act like caged animals, snarling in the checkout line at the grocery store, cringing in fear at imaginary crime waves in cities they’ve never visited, hurtling mindlessly through traffic, grabbing and hoarding at the pig troughs of Amazon and big box stores, conforming obediently to efficiency culture, or whimpering as they hunker down in the corners of their alienated, isolated lives.

Ordinary people seem caught between imbibing petulant and unscrupulous ideologies on the one hand and managing reeling shock on the other. As a result, no one I know is happy (unless they’re telling themselves a story—but more about that in a moment). It’s a rotten, mixed-up state of being, an exhausting confusion exacerbated by the oozing drivel fed to humans by their digital addictions fed by digital manipulation.

Lately I’ve been thinking about Muriel Glass, Seymour Glass’ beautiful, soon-to-be-bereaved wife in J. D. Salinger’s exquisite short story, “A Perfect Day for Bananafish.” She was “a girl who for a ringing phone dropped exactly nothing.” While I wouldn’t wish for Muriel’s insouciance, I long for her unflappability, her lack of jumpiness. Muriel’s undisturbed reaction to a jangling mechanical signal, an automated summons, is not only enviable, but also nearly extinct in an era when humans look at their phones incessantly while ignoring one another. I notice the agitation in myself, my sometimes-swiveling thoughts and my hair-trigger vulnerability to answering, seeking, or sending digital signals.

The digital framework of our lives isn’t going away; in fact—and as we all know—it is growing exponentially as the AI arms race between seven major corporations, in collaboration with the US government, drives toward its overweening ends. It’s neither possible nor smart to reject the fundamental conditions of the times, no matter how tangled and perplexing. Rather, it makes sense—it might be crucial—to explore and identify an approach to lived experience that scoops out some space for neurological autonomy within the mediated sphere. I have some ideas about this process, but first I need to ask you to take a little trip with me into my childhood experience with religion.

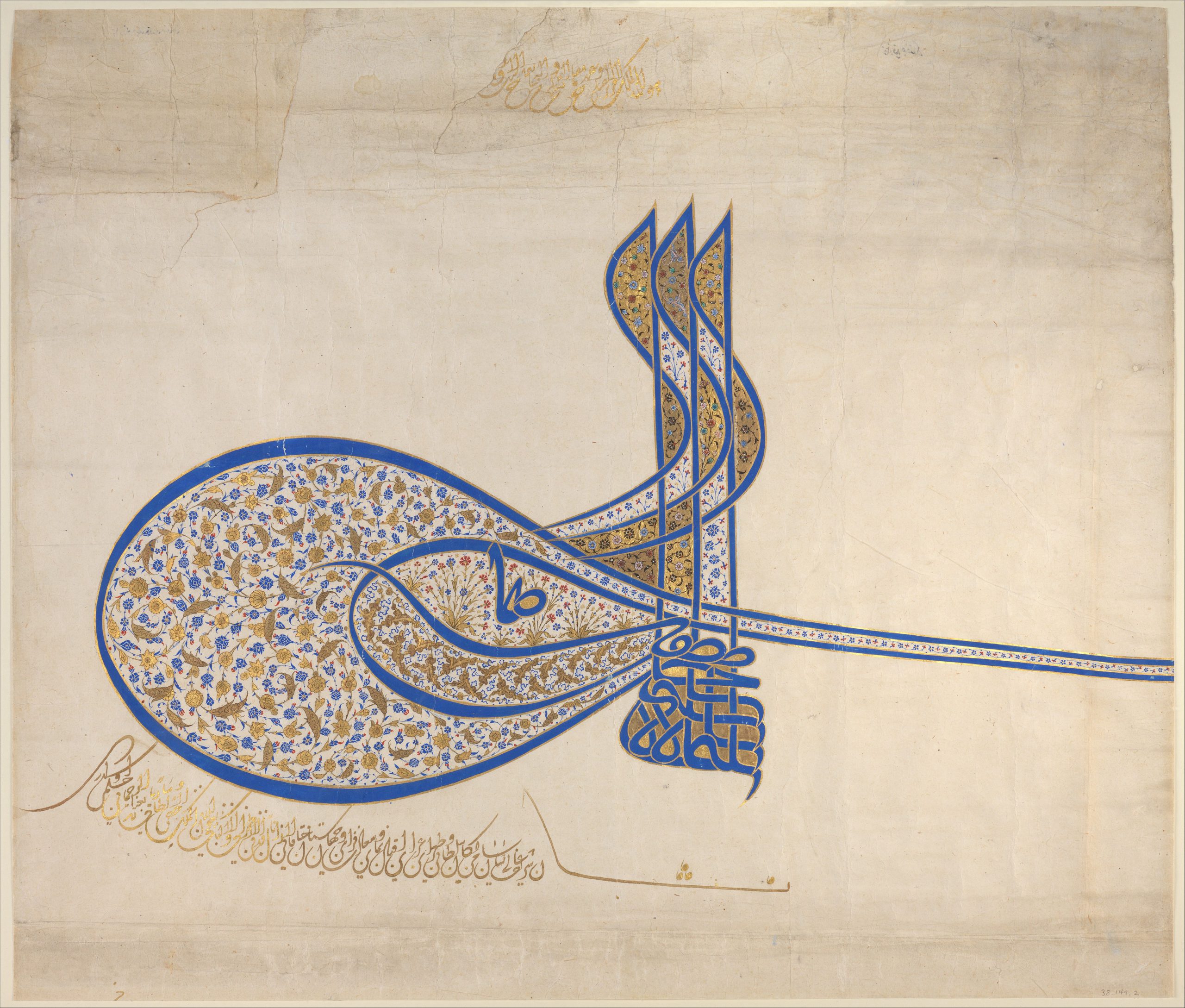

I was raised and have spent most of my life in proximity to Christian Science, a now-tiny religious denomination founded in the 19th century by an American woman, Mary Baker Eddy. Most notoriously, the religion advocates spiritual healing of physical disease through prayer and reliance on God (identified by seven abstract synonyms). Its Scientific Statement of Being begins, “There is no life, truth, intelligence, nor substance in matter. All is infinite Mind and its infinite manifestation…”2 The core effect of the doctrine that there “is no truth in matter” is to train individuals, through the denomination’s ecclesiastical structure, to reject their own sensory and perceptual awareness, to teach them skill in a self-mediation that negates their experience. The overlay of an artificial narrative about existence as “purely spiritual” is not only ideological but also denies conditions (the state of things) and firsthand knowledge.

As a child, I was taught to deny the senses and to “exchange the objects of sense for the ideas of Soul.” I was taught, essentially, to abstract my experience and to tell myself a story. If I scraped my knee, I was unscathed. If I was nearsighted, my focus was laser sharp. If I was lonely, Love was my companion. If I was grieving, I had lost nothing because the ideas of God are intact and immortal, having simply transmigrated to a different plane of existence. In other words, I learned to lie to myself rather than to live in, face, and cope with my own experience.

This layering of metaphysical self-talk over my actual perceptions had a two-fold effect. It taught me to believe in, to obey, and to grasp for “right thinking” as conceived in Christian Science and it taught me to block my own discernment. This training came primarily through the religion’s textual media, weekly Bible Lessons and self-study of the religion’s two books that function as its nonhuman “pastor,” the Bible and Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures. I then absorbed these lessons into persistent, automatic self-mediation.

My capacities to listen to myself, to grasp my own instincts or ideas, or to confront difficulties without fear were crippled. I spent years as a writer paralyzed by the idea that I wasn’t “supposed” to think about certain things, only to be told by the Christian Science practitioners (“healers”) to whom I turned for help that my writing would always include “redemption” and that I could always write about what was possible for me to safely contemplate. I was a terrified mother, who saw every sniffle in my unvaccinated children as incipient polio. I was addlepated, even if not fully aware of that fact.

This bewildered but persistent state was worsened by an insular community that shuns direct observation and statement. Writing and speech are highly coded for “rightness” and speaking openly is, if not taboo or offensive, at least ripe for correction, creating a deep, underground cavern of suppressed but highly charged emotions and memories. You’ve never had an odd conversation until you’ve spoken openly to a “true adherent” of Christian Science who is then shocked or offended and proceeds to “know the truth” about either what you’ve said or simply about you. For many years I tried strenuously to correct what I had been taught to believe were my own failures to “understand” since spiritual misunderstanding is the most common explanation for failure to heal.

None of this background is offered as a theological account of Christian Science. I have my bona fides—Sunday school from the ages of three to twenty, “class instruction” by a Christian Science teacher, and years of active self-study and church membership—but I’m happy to admit that I don’t get it (nor, at this point, do I want to). My purpose instead is to share a vivid example of cultural and textual mediation so intense that it scrambled my experience, functioning as a fractured lens through which I automatically viewed the world. For years I have wondered what my life and my mind would be like if I had never encountered Christian Science. It’s impossible to know because it has shaped me profoundly and naturally continues to affect me. It is, as a lapsed-Catholic poet once said to me, my context, a burden that everyone totes into adulthood. And it should be said that every context—religious, political, cultural, educational, or social—propagandizes at least to some extent and functions in some measure as a clouded or distorted lens. My experience with a quirky religion has become for me an object lesson in resisting mediation and indoctrination.

The human being is never beyond media because raw (or “pure”) sensation is transformed from inchoate experience to concrete concepts by a variety of means. These means are primarily neurological, although ideas remain intangible, subjective, and a function of learned patterns. A loop is created between sensory awareness, attention, and habitual responses mediated by habit, training, texts (digital, visual, audible, written, environmental), associations, and memory. Conclusions are the riders on a merry-go-round of brightly adorned horses gliding up and down on the poles of input and output.

Navigating inevitable mediation is a daily, Sisyphean task, but one whose circularity has to be accepted. In my case, it has meant a conscious coming to my senses—a return to the sensate with its unpredictable, idiosyncratic, but authentic lived experience. It has meant the conscious rejection of disembodied awareness, whether that awareness emerges from the myriad, seductive digital signals emitted through phones and computers or from the rigidly ideological cultural texts of a religion and religious culture. I have learned the hard way that such disembodied awareness—living “in my head” one way or another—becomes an abstraction embracing confusion as an illusion of clarity, a failure of imagination, and a failure of empathy.

Returning to the sensory as a baseline also doesn’t mean “mindfulness” or some practice of minutely self-conscious attention to my body’s sensations. Rather, it means accepting the messiness of my sensory humanness as an aspect of resistance to having my thoughts delivered to me whole cloth from an external source. It means recognizing that at any given moment both my perceptions and my conclusions may be wrong. I can sit with poet Wisława Szymborska’s words in “Returning Birds”: This spring the birds came back again too early/ Rejoice, O reason: instinct can err, too.3

It means noticing what I am thinking, feeling, experiencing and asking questions about these perceptions. Had I had this sensory immediacy when I was a young mother, for example, instead of trying to conform to a religious practice and papering over my fears with external (mediated) doctrinal narratives, I could have observed those fears in my body and in my ideas. Recognizing what I was truly sensing and thinking would have enabled me to navigate the decision-making those fears necessitated, to change course and protect my children from communicable diseases through vaccination. But I couldn’t have that conversation with myself until I could distinguish between the habitual response queued by my cultural context and my more complicated and authentic experience.

To come to my senses means accepting the plasticity of the brain—its capacity to change its structure and function because of input and experience. I love the fact that, as literacy advocate and scholar Maryanne Wolf has pointed out, every part of the brain lights up when we have an ah-ha moment during close reading (for years I tried to get my teaching colleagues to accept that deep reading was “experiential education”).4 Reading a physical book, holding that book in my hands without the distractions of music or streaming images, allowing the act of following the words to ignite the mind, is one way of returning to myself, ironically through the mediation of the printed word. Every blossoming illumination is ineffable and leads to a series of branching paths of subsequent, opposing, or coordinating insights.

It may be helpful here to illustrate what I mean by “coming to my senses.” These processes emerge from my own practices and training. They’re fairly simple, but they function to make visible to me the flow of my perceptions—which, again, are received initially via sensory information—in ways that are both significantly less reactive and less unconscious than the mediated states in which I find myself.

I’m sound-sensitive, but I’ve cultivated a practice of silence. For the most part, as I go through my days, there’s no radio, TV, streaming music, no earbuds or noise cancelling headphones. I’ve always loved a story that the visual artist Ray Kass told me about his visit with John Cage to an anechoic chamber at Virginia Tech University when Cage was the featured artist at the Mountain Lake Workshop.5 There’s no sound in an anechoic chamber, except that Kass said that the two men could clearly hear their cardiovascular systems rushing and whooshing through their bodies.

Drawing is, for me, another way to come to attention. The always surprising and humbling process of trying to see accurately—of becoming aware of forms, details, spatial relationships, characteristics in some small piece of the world that I hadn’t seen when I was merely looking—has always been both calming and almost irradiating. It doesn’t matter whether I “can” draw. Rendering isn’t the point; the point is the physicality of it, the feeling of the pencil in my hand, the tension of the graphite against the paper, working with my sight to take in the details and translate them not into a beautiful drawing but into something I have truly seen—and thus remembered and, in a sense, touched.

When I was in graduate school, I studied with the writer George Garrett. George used to talk about “the sensuous surface of the work” in writing fiction. A web search about the senses in creative writing won’t bring up this phrase but will bring up advice about using “sensory imagery” in writing. Sensory imagery is something AI can serve up for you, but the “sensuous surface” of the world is something that has to be phenomenologically experienced. To be affective, the human being’s own senses have to be put to physical work, bringing into being the flip side of reading, the mediation of the senses bringing the writer to redolent—and hopefully insightful—words.

And I do find it necessary to turn off digital and electronic mediation as much as possible. I have removed myself from social media platforms and returned to communicating directly with others, one to one and not en masse. I like technology and I use it, but intentionally in ways aligned with those moderating and resistant practices described by Jenny Odell in her brilliant book How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy.6

As I grow older, I have come to see my senses as the means by which I can both accept my own mortality and remember others’ pathos. Xi and Putin’s nightmarish discussion, caught on a hot mic,7 about living forever through organ transplants recalls the dehumanization of the organ harvesting in Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go, the literal somatic mediation of an organic body to serve someone else’s goals. But the vulnerability of the self, perceived through the body’s tender senses, is resistant to this kind of cruel and indifferent selfishness. This human body is my organic machine, the one I’ve got, the imperfect one that changes, the one I need to use to understand my own consciousness and the world around me, until I’m no longer living.

I have come to accept that this state of being is in motion, constantly changing but not necessarily chaotic or addled. Rather, it reflects the endless meaning-making in which mediation—the arbitration of my thought by internal perception and/or external messaging—and its invitation to absolute conclusions can be resisted. Contemplative skepticism has become my faith, which makes me feel just a little less crazy.

1. Frank Bruni, “The Unchecked, Unbalanced Reign of King Donald,” The New York Times, September 1, 2025.

2. Mary Baker Eddy, “The scientific statement of being,” Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures (Boston: Christian Science Board of Directors, Copyright 1906, by Mary Baker G. Eddy, renewed, 1934), 441.

3. Wisława Szymborska, “Returning Birds,” Poems New and Collected, trans. Stanisław Barańczak and Clare Cavanaugh (New York: HarperCollins, 1998), 96.

4. Maryanne Wolf, interview by Ezra Klein, The Ezra Klein Show, The New York Times, November 22, 2022.

5. The Mountain Lake Workshops, originated by Ray Kass, represent a longstanding collaboration between significant visual artists and the surrounding community.

6. Jenny Odell, How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy (New York: Penguin Random House, 2020).

7. Oliver Holmes and Pjotr Sauer, “Hot mic catches Putin and Xi discussing organ transplants and immortality,” The Guardian, September 3. 2025.