[drop-cap]

The week before Democratic Party delegates arrived in Chicago in late-August 1968 for what promised to be a combustible national convention—with delegates, antiwar protesters, and the Chicago police department assembling for uncertain battle—the Saturday Evening Post published a “Points West” column that departed from the magazine’s usual snug-to-the-center politics, not to mention the expected politics of its author. “On Becoming a Cop Hater” recounted how the author—primed as a child not just to obey the police but to consider them her “only friends”—came to distrust cops and bristle at their twisting of the truth. The piece was accompanied by an illustration, in a hyperbolic style more typical of the underground press, of a Janus-headed cop—one face placid and with a heart painted on its cheek, the other barking in rage with teeth bared and eyes squeezed shut.

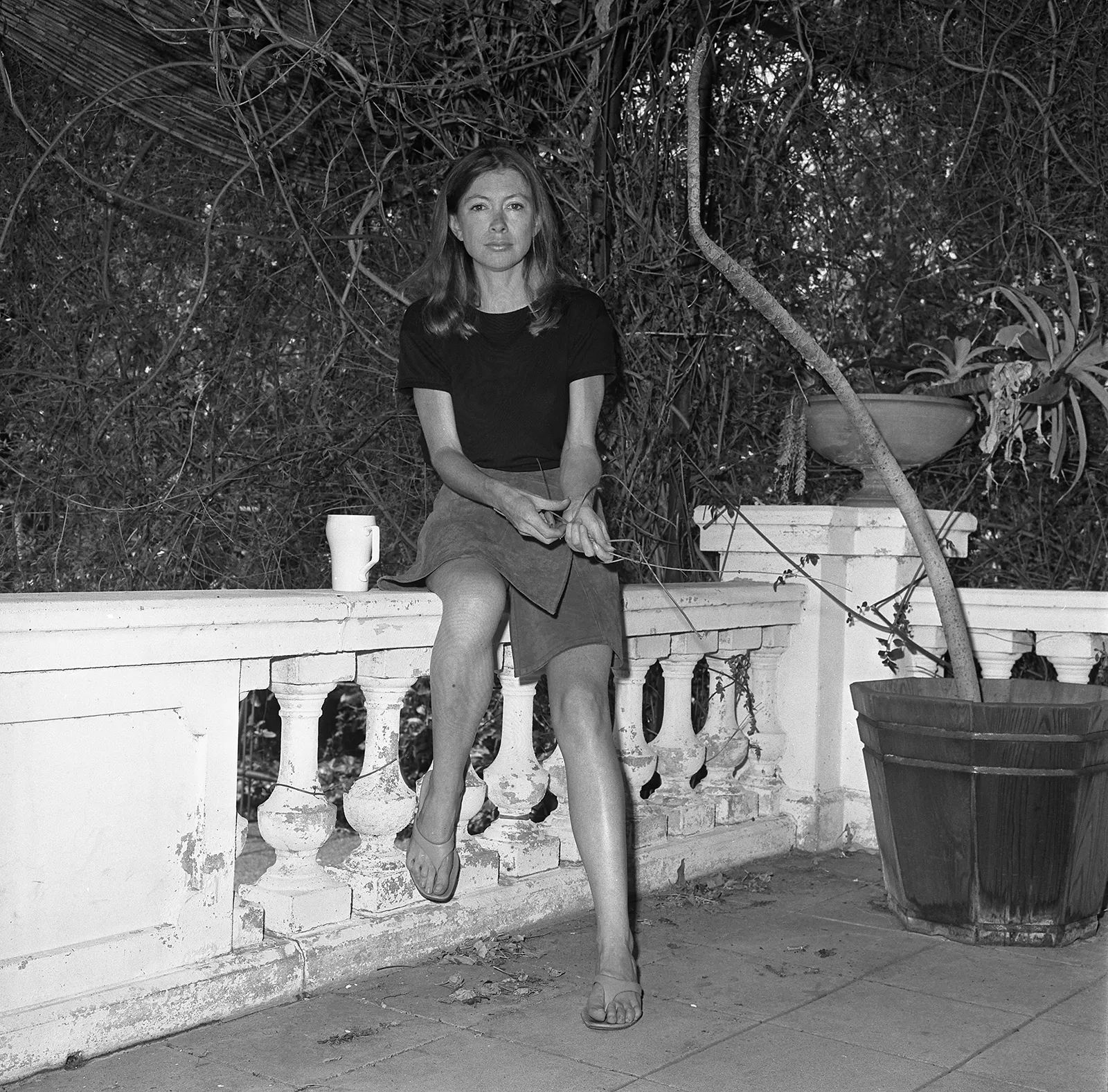

Its author was Joan Didion, a regular Saturday Evening Post contributor; the magazine had featured her now-classic essay “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” with its disturbing portrait of the Haight-Ashbury counterculture as a moral vacuum, as its cover story the previous fall. From one angle Didion could not have timed “On Becoming a Cop Hater” more perfectly. Its argument about police violence—that it was indiscriminate and blinkered—was validated by the ensuing events in the streets of Chicago: When a motley crowd of 10,000 gathered outside the DNC convention to protest the party’s complicity in the war in Vietnam, the Chicago police force treated them as invaders rather than people exercising their right to assemble. On the night of August 28, police kettled the protesters into a small area outside the Conrad Hilton Hotel and, in full view of convention delegates, assaulted them under color of authority. According to the Walker Report, the official autopsy of the events outside the convention, this “unrestrained and indiscriminate police violence” was “made all the more shocking by the fact that it was often inflicted upon persons who had broken no law, disobeyed no order, made no threat.”

Despite its immediate resonance, however, Didion chose over the course of her career to shed “On Becoming a Cop Hater” rather than claim it. Ten years later, it went uncollected in The White Album (1979), which drew upon seven of the other “Points West” columns she wrote for the Saturday Evening Post. More strikingly, “On Becoming a Cop Hater” remains the only one of her fourteen “Points West” columns not to be incorporated into either The White Album or her late-career anthology Let Me Tell You What I Mean (2021), which scoured thirty years of her writing for unpublished plums. Why did Didion choose to re-publish, say, “A Trip to Xanadu”—a parallel story of disenchantment, fixed on William Randolph Hearst’s San Simeon and its promise of infinite luxury—but not “On Becoming a Cop-Hater,” which, if it had appeared in Let Me Tell You What I Mean, would have put her older work in dialogue with Black Lives Matter and the protests around George Floyd? Why let the essay fall into obscurity?

There are other pieces from Didion’s 1960s catalog that have not been republished and are now mere historical curiosities, of interest only to hard-core Didionphiles. It’s not surprising, for instance, that Didion memory-holed “The Big Rock Candy Fig Pudding Pitfall,” her shambolic account of how, desperate to prove herself a “‘can-do’ kind of woman” in the fall of 1966, she committed herself to making twenty hard-candy topiary trees and twenty figgy puddings. (For the record: with the puddings Didion got no further than the purchase of twenty pounds of figs.)

But “On Becoming a Cop Hater” is vintage Didion, textbook in its method (the interrogation of preconceived ideas through precise observations of everyday encounters) and its tenor (the search for integrity in a corrupt and disenchanted world). The prose is taut and controlled, its ending analysis a sharp extension of George Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language” to encompass the particular dialect of copspeak.

The essay moves through three parts, from an opening scene of conflict to a middle section that narrates how Didion gradually grew to distrust police, and onto a last section that reflects on the crumbling of police authority and credibility. It launches with a scrupulous reconstruction of a false arrest that Didion witnessed on Honolulu’s Kalakaua Avenue “one early evening in the late spring.” A driver in a Thunderbird almost hits two “boys” in a crosswalk; one of the teenagers may or may not have responded with some words (Didion does not know, and records that she does not know); and the driver of the Thunderbird responds “malignantly” and with just as little vision as he exhibited in almost running them over:

“Stinking hippies,” he screamed, jumping from the car. “Burning your draft cards, you should’ve burned Germany, you should’ve burned Japan, stinking hippies.”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about, Mister,” one of the boys said. He was wearing a blue suit and a white shirt, and his blond hair was about as long as the average college freshman’s. “I got my draft card.”

“Stinking cowards, stinking hippies.”

“Good for him,” said an old man behind me. Quite a crowd had gathered by then, most of them the retired and the conventioneers who wander aimlessly up and down Kalakaua Avenue in the off seasons, and, when two police officers finally drove up, the crowd clapped.

The reckless driver leaves the scene; a police officer grabs the boy in the blue suit and arrests him for “resisting an officer”—his crime apparently that he had the audacity to say “I didn’t do anything” to an officer who had told him “Don’t talk back.”

At this point in the unfolding drama, Didion crosses the line from observer to participant—acting not willfully but rather via her instinctive sense of injustice and reflexively echoing the words that led the boy to be arrested: “‘But you can’t take him in,’ I heard myself saying suddenly, ‘He didn’t do anything.’” She touches a police officer on his arm to attract his attention, and he “recoil[s] as if touched by a snake.” His partner springs forward and raises his arms in a “defensive karate position” against Didion. The aggression is as theatrical as it is absurd. Didion notes that she is a mere five-feet-two and weighs 91 pounds.

Like the errant Thunderbird driver and the crowd of retirees who see “stinking hippies” where there’s just an average American teen (wearing a suit no less!), the police seem committed to not seeing what is in front of them: “Both of them fixed their eyes just over my head in that gaze peculiar to police officers and troops on review.” The opening scene ends on a downbeat, with Didion taking in the consequence of these acts of flawed witness: “I last saw the boy in the back of the patrol car, on his way to the precinct house.”

At this point, Didion fills in “a few things about myself” so that her readers can understand where, exactly, she is coming from. She was raised, she explains, “in that stratum of the society which teaches its children that the police are not merely their protectors but, in a world of hostile strangers, perhaps their only friends. When I thought of the police, certain images sprang obediently to mind.” Here “obediently” is the keyword. Her imagination itself had been schooled to obedience, trained to project benign scenarios of policemen leading small children across an intersection or otherwise coming to the aid of those who have not reached the age of reason: “Policemen were there to rescue lost balls, and kittens, and, were a child to drop her ice-cream cone, a policeman would dry her tears and buy her another, with a nickel from his own pocket.” These images of ever-benign policemen revolve around children and are likewise tailored to the ingenuous mind of a child, one that believes what it sees and reads in books. “I had never actually come into contact with such a policeman,” Didion adds sardonically, “but I knew all that to be true because I had seen pictures of it happening, in school readers and coloring books.”

This conditioning from her childhood was so strong, Didion admits, that until “quite recently” she had held onto the illusion that no policeman would treat her roughly. “Even when I knew myself to be in technical violation of the law,” she recalls, “I was confident that the police, should they by some bizarre error apprehend me, would recognize my essential ‘niceness’—i.e., my status as a daughter of the lawful and propertied bourgeoisie— and deliver me to my doorstep with a friendly and, well, respectful admonishment.” In a touchingly frank moment of self-scrutiny, Didion ties this benign view of police to “some unexamined snobbery” within herself. In the cocoon of her unexamined privilege—that place of feeling herself beyond suspicion—she had been happy to lead an unexamined life.

Didion offers this personal history to establish that she was “neither born a cop hater nor did [she] become one by way of some dramatic venture into the unlawful.” Her mind has been shaped “by way of an accumulation of small encounters, insignificant confrontations” like the Kalakaua Avenue incident; it’s the pressure of her lived experience that has forced her to discard the second-hand lessons of the primers and coloring books.

She offers a brief catalog of damning incidents. When she phones the police to report that a female driver has suffered a grievous accident and is “intermittently unconscious and screaming,” no police car is sent, and the “desk man” asks her if the driver was drunk. Her friends get stopped for traffic offenses and are subjected to “extensive inquisitions.” She notices a pattern of unequal enforcement and profiling: “every time I saw a cop stop a car on the Sunset Strip, he was stopping either a juvenile or a Mexican.” She registers the customary posture of the police—“the belligerent crossed arms at police lines”— and how they see “the enemy” as “anyone not a cop, not on the force, not in the life.”

In the last section of her piece Didion pivots to a more writerly register, drawing out how policemen have become unreliable narrators in the public square. She takes Orwell’s insight from “Politics and the English Language”—that “the decay of language” is tied to the “defence of the indefensible”—and applies it to the phenomenon of coptalk, its features and its tone. The passage is worth quoting at length:

I began to distrust the baroque obfuscation of language common among the police, began to see it not as an amusing foible but as a quite purposeful barrier between the cop and the enemy. I watched cops caught in stupid lies. I started hearing a tone in police voices, a tone that made no distinction between the criminal and the noncriminal, between the Mafia narcotics dealer and the college boy with two sticks of marijuana in his glove compartment. ‘Move on, sister,’ the tone said, and ‘We aren’t running a hotel, lady.’ (I was told that by the desk sergeant in a jail where I was trying to arrange bail for a boy who had just been arrested for possession of marijuana. ‘We aren’t running a hotel, lady,’ and then: ‘I can give him a message if I feel like giving him a message, not otherwise.’) It was a tone calculated—whether by deliberation or reflex—to threaten, to harass, to humiliate, to bully. I read not long ago that the police call this tone, this stance, ‘aggressive prevention.’ Perhaps all they are preventing is the possibility of their own credibility.

In the last line, we hear the puffed-up language of “prevention” deflating with a whoosh, as Didion turns the term against those who wield it.

That last one-liner draws together what has come before in the passage: Didion’s quick anatomy of the conventions of coptalk, from its indiscriminate address (with everyone a potential “enemy”) to its put-upon and bullying tone. The section she places within parentheses is particularly choice—a vignette that might seem confected for a Hollywood film if it weren’t authenticated by Didion as her own experience, and one that offers a surprising image, within her oeuvre, of Didion as someone who cares enough to involve herself, to arrange bail. In the eyes of police, she suggests, an intercessor is a nuisance—and someone with no more rights than the accused.

The parenthetical section also crystallizes the final position of Didion within the essay: she is a person who, by background and temperament, would have preferred to trust the police and the system of public order that they administer but now feels herself pulled into intellectual sympathy with those in the police’s crosshairs. Didion being Didion, for all her “cop-hating” she cannot join in the sloganeering of those who protest police violence, but, again, in a rare moment for her, she shows a generosity towards those who have been pressed by their experience, she suggests, to “start thinking in such slogans.”

The piece concludes with just this balancing act, Didion drawn to credit protesters even as she maintains daylight between herself and the “New Left provocateurs” who galvanize a movement with phrases like “police brutality”:

I know that ‘police brutality’ is a slogan, and that like all slogans, it corrupts and coarsens the perceptions of those who use it. But expose someone to enough ‘aggressive prevention,’ and she is going to believe the New Left provocateur who says the police broke his back, going to believe the country singer who says he was worked over when he was drunk. I do not go around using words like ‘blue Fascism,’ but it has been a very long time since I thought of a cop as a friend in blue.

The phrase “a very long time” seems a bit overstated: the incidents Didion evokes in her essay (involving “hippies” and marijuana busts) seem to date, at most, from a few years before its 1968 publication. Perhaps, if we wish to be generous, we might say that Didion was referring to a span of psychological rather than chronological time—the distance between The Beatles’ Revolver and The White Album rather than, say, “two years.”

In any case, we can deduce that at this moment in the summer of 1968, Didion wanted to stress that, when it came to police violence, she was no naif.

“On Becoming a Cop Hater” remains the only one of Didion’s Saturday Evening Post columns never republished in her essay collections. Why did she choose to shed it?

A decade after “On Becoming a Cop Hater,” with the publication of The White Album, Didion made profitable use of a very particular set of the fourteen pieces she had written as a regular contributor to the Saturday Evening Post in 1968. The White Album ratified her place as an American essayist of the highest rank (“Nobody writes better English prose than Joan Didion,” critic John Leonard judged), and its title essay became an instantly canonical reflection on the turmoil of the late 1960s: “the best short piece… on the late 1960s that I have yet read,” said the reviewer in the New York Times Book Review. Didion had “staked out California” and witnessed how LA had devolved, in the words of historian Eric Avila, into a “moral dead end, where the underlying values of industrial capitalism—hard work, thrift, diligence, and delayed gratification—had given way to the hedonism and narcissism of twentieth-century consumer capitalism.” On the commercial end, The White Album sold so well as a hardcover book—90,000 in its first printing alone—that Didion was able to sell the paperback rights at auction for $247,500, or over $1 million today.

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” Didion famously opened “The White Album,” and, as she herself underlined, there’s always much at stake in the question of which particular story a writer selects from the spectrum of possibilities. Though the endless recirculation of that sentence has softened its meaning—rendering it as something like “human beings are storytelling animals”—in the essay itself it expresses a dire, existential skepticism. The act of storytelling, Didion suggests, has life-or-death stakes (we tell ourselves stories in order to live, not just to entertain ourselves or locate ourselves in a community) even as the foundations underneath such storytelling are shakily unstable (the stories we tell ourselves are chosen to suit ourselves, not because they are more true).

In “The White Album,” Didion confessed to having been unsettled by the discovery that there was no providential or final arrangement to the “flash pictures” by which her mind condensed the stories of her life; the stories she had been “telling herself to live” no longer had depth of meaning or a rightful place in a larger storytelling arc. “I was meant to know the plot,” she wrote, “but all I knew was what I saw: flash pictures in variable sequence, images with no ‘meaning’ beyond their temporary arrangement, not a movie but a cutting-room experience.” Which is to say: Rather than being allowed to sit back and watch the movie of her life, Didion was alarmed to be pressed into serving as its editor, in charge of every cut and splice.

It can be instructive, then, to examine The White Album and consider how she worked as her own editor, fitting many of her older pieces into the fixed “arrangement” of the book and leaving others on her cutting-room floor. As a whole Didion snipped out of her collection those pieces that would have recorded her more sympathetic moments of engagement with the New Left and the counterculture, and stitched in those that crystallized her portrait of the late-60s as a time of aimlessness, thoughtlessness, and collective nervous breakdown.

To construct the title essay, Didion pulled from three Saturday Evening Post columns that had sketched California’s counterculture and left-wing activists in a damning light. She excerpted from her piece on the non-event that was her visit to a Doors recording session (“unspecific tensions seemed to be rendering everyone in the room catatonic… There was a sense that no one was going to leave the room, ever”); her piece on a visit to Black Panther Huey Newton in Alameda County Jail, in which she stressed the banality of Newton’s rhetoric of revolution (“almost everything Huey Newton said had the ring of being a ‘quotation,’ a ‘pronouncement’ to be employed when the need arose”); and her piece on the student activists at San Francisco State, in which she observed that “in the minds of even the most dense participants” there was no constructive goal being pursued (“Disorder was its own point”). Across these three pieces, she is the reporter who is intrigued enough to send herself into the cultural and political maelstrom but then brings back the news that there is nothing much of substance to report—just an atmosphere of anomie (the Doors), an empty performance of left-wing rhetoric (Huey Newton), or “scenes of industrious self-delusion” (SF State).

In the collage of “The White Album,” Didion interleaved these “Points West” excerpts with two other sets of stories. There were, first, those that touched on acts of murder near the “senseless-killing neighborhood” of Hollywood where Didion lived in the late-’60s—the story of the teenage hustlers Paul Robert Ferguson and Thomas Scott Ferguson, who had murdered silent-film star Ramon Navarro in his Laurel Canyon home; and the story of Linda Kasabian, the prosecution’s star witness in the Manson trial (Didion visited her in prison and picked out the I.Magnin dress she would wear for her first appearance in court). The Ferguson and Manson murders serve for her as signs of the times and confirm her suspicions of the larger world she inhabits. “I read the transcript several times,” she says of the Ferguson brothers’ trial, “trying to bring the picture into some focus which did not suggest that I lived, as my psychiatric report had put it, ‘in a world of people moved by strange, conflicted, poorly comprehended and, above all, devious motivations’.” The news of the day validates what a psychiatrist might diagnose as her paranoia—her sense that the Ferguson brothers and the Manson family are not outliers but all too typical in a world where “poorly comprehended” motives are conscripted to “devious” ends. In her world, people are somehow both going mad and titillated by their descent into madness: “A demented and seductive vortical tension was building in the community. The jitters were setting in. I recall a time when the dogs barked every night and the moon was always full.”

The second set of stories revolves around Didion’s mental and physical deterioration in the late-’60s. It’s this strand within “The White Album” that makes it such an advance, on a stylistic level, over her earlier “Slouching Toward Bethlehem.” Whereas that essay relied on a deadpan mode that deflected attention from its narrator’s state of mind, “The White Album” is served by its tense blend of unreliable and reliable narration: Didion paints herself as extremely unreliable during the late-’60s (the subject of the essay) but puts a stamp of indisputable authority on the larger essay itself, which is composed from a distance of a decade. So, for instance, on the side of her unreliability, we know that a world where “the moon was always full” is an astronomical impossibility, even as it stands as an objective correlative to what Didion perceives as a “lunatic” world. In a striking gesture of authorial self-revelation, Didion even gives us a harsh and lengthy excerpt from a clinical report written by her psychiatrist, in which he diagnoses her as someone who has “alienated herself almost entirely from the world of other human beings” and whose “basic reality contact is obviously and seriously impaired at times.” Didion’s portraits of Huey Newton and the SF State activists, therefore, come with an asterisk attached to them, tagged as thickly filtered (and in a way that they would not have been in their earlier published form, as “Points West” columns in the Saturday Evening Post). Given that, as her psychiatrist suggests, Didion “feels deeply that all human effort is foredoomed to failure,” we should not be surprised that she frames their political protest as doomed; any activist, it seems, would produce the same response in her.

But while Didion foregrounds her late-’60s mental crisis in “The White Album,” the essay gains its authority from its narrative distance from that crisis. The narrator has left behind “the 1960s” as well as her 1960s in order to write it: in the essay’s coda, she recalls how she moved from her house in Hollywood to “a house on the sea” (a Malibu beach house, actually, but “house on the sea” has a nice ring to it, suggesting an escape to a more remote, quasi-mythical location). She notes approvingly that, although her ocean-facing home originally bore traces of the 1960s, “between the power saws and the sea wind the place got exorcised.” How fortuitous when a home renovation does double duty as an exorcism! As the datemark at the end of her essay (“1968-1978”) underlines, she has composed her essay from a place dispossessed of the historical demons that the essay itself evokes. And her late-’70s self has carefully composed it indeed, arranging her particular assortment of “flash pictures” in an easily legible arc. Placed next to one another, her stories of rock stars, radical activists, murderers, and the mentally unwell insinuate a certain guilt by association, with the counterculture and New Left implicated in the charges of senseless violence and mental dissociation. The “1960s” sit in the dock, indicted by a prosecutor who can claim a certain extra authority as a victim of the accused.

Didion the narrator-prosecutor appreciates, too, the power of a closing statement: “The White Album” plays with chronology, saving what Didion claims as her most intense piece of historical evidence for the end of her essay. Just before the essay’s coda, she relates a clinical visit to a neurologist, who diagnoses her with multiple sclerosis. It is a diagnosis, Didion suggests, that “had no meaning” because it was merely an “exclusionary diagnosis” (a diagnosis made only from ruling out other alternatives), and because it had little predictive power (“I might or might not experience neural damage all my life”). Didion italicizes the conclusion we’re meant to draw: “The startling fact was this: my body was offering a precise physiological equivalent to what had been going on in my mind.… In other words it was another story without a narrative.”

Up to this point, the essay has been tracking the mental crisis of Didion and viewing it as both the expression and the product of the historical crisis of the late-’60s: “an attack of vertigo and nausea,” she writes early in the essay, “does not now seem to me an inappropriate response to the summer of 1968.” At this point Didion shifts her approach. For those who might question the linkage between her mental crisis and the larger historical crisis—perhaps the moon was not full every night in the late-’60s; perhaps Didion’s attack of vertigo and nausea sprang more from her core personality than from the spirit of the times—Didion offers as her clinching piece of evidence her physical body, which not only wears the ravages of the late-’60s but also has developed, she suggests, the precise illness that registers the narrative unmooring of the era. Her body knows the score, and you better believe it.

For a biographically and historically-minded reader of Didion, however, this section rings a false note. Though she places this visit to a neurologist at the tail end of her essay, thus turning it into the culmination of her meditation on the late-1960s, the actual visit took place, according to her biographer Tracy Dougherty, in a Beverly Hills doctor’s office in the spring of 1965—over a year before the Doors released their first album and the Black Panther Party first formed in Oakland, two years before the activists at San Francisco State staged their first sit-in, and so on. We are left to wonder how her body could have registered the illness of the times before the historical moment began to coalesce. The “startling fact” becomes a startling fudge.

In its rebuke of the 1960s spirit of cultural and political dissent, “The White Album” essay set the tone for the rest of Didion’s collection. Across The White Album, activists and their supporters were dressed down variously as self-serious, ideologically blinded, and profoundly immature. In an essay bearing the ironic title “Good Citizens” and featuring material from another 1968 “Points West” column, Didion skewered liberal Hollywood’s support of the Civil Rights movement: “the public life of liberal Hollywood comprises a kind of dictatorship of good intentions… a climate devoid of irony.” In a scathing piece on the “women’s movement” as a whole—Didion did not distinguish between liberal feminism and Women’s Liberation—she attacked it for creating a cult of victimhood (the movement’s “imagined Everywoman” “was everyone’s victim but her own”); for resorting to poor argumentation (its analysis was “dense with superstitions and little sophistries, wish fulfillment, self-loathing and bitter fancies”); and for having an “aversion” to “adult sexual life itself”—part of her more general argument that feminists sounded like “perpetual adolescents,” “scarred not by their class position as women but by the failure of their childhood expectations and misapprehensions.” Feminists may have thought they were theorizing the problems of sexism and sexual violence but, in Didion’s analysis, they were acting out their frustrations with the dimensions of adult life.

The White Album ended where it began, with a valediction to the previous decade via a section entitled “On the Morning After the Sixties.” Here Didion paired a reflection on the peaceable yet precarious world to which she had repaired in the 1970s—“Quiet Days in Malibu”—with the essay that gave the section its title. Didion there suggested that her generation, the generation of the 1950s, was constitutionally allergic to participating in large-scale political action—or, as she put it, “distrustful of political highs.” Addressing why her generation was “silent,” she ruled out two main explanations—that they “shared the period’s official optimism” or “feared its official oppression.” Rather, they “were silent because the exhilaration of social action seemed to many of us just one more way of escaping the personal, of masking for a while that dread of the meaningless which was man’s fate.” Didion’s language had existential accents—the hard language about confronting one’s fate, the reference to Andre Malraux’s novel about a failed communist insurrection—but it turned Sartre upside-down, offering a whiff of existentialism but stripping away its main ethical impulse. Social action was, in Didion’s eyes, a way to dodge existential dread rather than a way to address it by fashioning a meaningful life; it was done for kicks, or “exhilaration,” rather than for the sake of justice or recognition.

We are left to wonder how Didion’s body registered her multiple sclerosis—ostensibly the illness of the times—before the historical moment began to coalesce. Didion’s ‘startling fact’ becomes a startling fudge.

Strikingly, Didion herself dodged an opportunity here to reflect on the main issues which had animated the activists of the 1960s, such as racial inequality and the war in Vietnam. Instead she returned to the issue of her temperament and how it bound her to remain an observer rather than a participant: “If I could believe that going to a barricade would affect man’s fate in the slightest I would go to that barricade, and quite often I wish that I could, but it would be less than honest to say that I expect to happen upon such a happy ending.” Didion explained her quietism as her way of being true to herself, of honoring her lack of faith in collective action. Given that she harped often on the need for others to grow up, to throw off the illusions of their youth and embrace the complexities of the world, it’s curious that Didion adopted this particular line of defense for her own behavior—that she was a creature of the 1950s and always would be.

Of course, it’s easier to defend a course of inaction if one hides from view what has spurred others to join a movement or, in Didion’s phrase, to go to a barricade. This is why Didion’s editing strategy, in composing The White Album, strikes me as a falling-away from a challenge, a retreat from the acknowledgment of moral and political complexity. It was not necessary, in explaining her family’s move to a beach house in Malibu, to demonize the world she had left behind.

In fact, in several Saturday Evening Post pieces that she chose not to include in The White Album, she had taken pains to register some of the complexities of the late-’60s moment. While The White Album tends to treat protesters in isolation, outside the context of the institutions they were protesting, in these pieces Didion directs her withering gaze at those very institutions. In “Alicia and the Underground Press,” she writes that mainstream American newspapers leave her “in the grip of a profound physical conviction that the oxygen has been cut off from my brain tissue, very probably by an Associated Press wire.” They rest on a “quite factitious ‘objectivity,’” a pretense belied by the “very strong unspoken attitudes” that saturate their prose and whose denial “comes between the page and the reader like so much marsh gas.” Didion confesses that, by contrast, she finds underground newspapers refreshing: while they might be “amateurish and badly written,” “they talk directly to their readers” and their “common ethic lends their reports a cogency of style.” If one wishes to know what is happening in the world, it is better, Didion suggests, to read the “strident and brash” underground press than the dissemblingly gray and muted sentences of The New York Times.

Less of a broadside, “Fathers, Sons, Screaming Eagles” is a surprisingly affecting report from the twenty-third annual reunion of a World War II Army division, the 101st Airborne, in Las Vegas. Against the backdrop of the precisely controlled environment of the Stardust Hotel—“inside it was perpetually cold and carpeted and no perceptible time of day or night”—Didion has a haunting encounter with a veteran who shares with her a newspaper clipping, preserved scrupulously in clear plastic, about his son, now missing in action in Vietnam. It features a “snapshot of the boy, his face indistinct in the engraving dots,” and Didion reports that the “indistinct face of the boy and the distinct face of the father stayed in my mind all that evening, all that weekend, and perhaps it was their faces that made those few days in Las Vegas seem so charged with unspoken questions, ambiguities only dimly perceived.” Maxwell Taylor, one of the men responsible for the prosecution of the war in Vietnam, addresses the convention and tries to banish those ambiguities, linking the press reaction to the Tet Offensive to the press reaction to Battle of the Bulge. But Didion holds onto them: the piece concludes with her speaking to a veteran with a teenaged son, who might be drafted in a few years. The veteran speaks for the hesitancy of those asked to sacrifice for this new war effort: “I never thought of dying then… I was eighteen, nineteen. I wanted to go, couldn’t stand not to go… Now I’ve got a boy, well, in four years maybe he’ll have to go…. I see it a little differently now.”

Didion as engaged reader of the underground press, Didion as skeptic of the costs that the Vietnam War was inflicting—in these pieces we see her reckoning with the crumbling credibility of the mainstream institutions that the protesters of the 1960s had themselves assailed. And then there was “On Becoming a Cop Hater,” where Didion revealed not only that she agreed with the New Left’s critique of police violence and police manipulation of the truth, but also that she herself had been changed through her multiple encounters with police: she now wore the identity of “cop hater” (a fact hammered home by the piece’s title). Didion was generally as allergic to labels as she was to slogans, but in that piece she had—in the spirit of the underground press—made her point of view explicit and claimed an identity forthrightly oppositional to those in authority.

The White Album would have certainly been a less ideologically legible collection if it had included any of these three pieces, and it might have had a less welcome reception. Rather than assuming its streamlined shape as a farewell to the pain and follies of the earlier decade, it would have had a few ends sticking out at odd angles, reminding the reader of why the political life of the 1960s had been so agonizing to so many and why the decade was not so easy to file away. Naturally Didion had every right as a writer to include the particular essays that she did and to exclude others. But there’s a case to be made that, by sanding down the edges of her own body of writing—by not setting “On Becoming a Cop Hater” against “On the Morning After the Sixties” and trusting the reader to handle the contrapuntal movement, or the dissonance—she engaged in the very forms of simplification that she had attacked throughout her career as a writer.

While it’s true that Didion never republished “On Becoming a Cop Hater” in any of her own collections, it’s not quite true that it was never republished. In 1971, it appeared in a Random House reader aimed at introductory college writing classrooms, bearing the early-Seventies-scented title Read On, Write On. The advertising copy for this classroom reader promoted it, cheekily, as all things for all readers, acknowledging with a kind of jocose hysteria the faultlines on college campuses at the time. In the journal of the National Council of Teachers of English, Read On, Write On was plugged as a “way out, conservative, relevant, traditional, prescriptive, permissive, issue-oriented, language-oriented, rhetoric-based, discussion-centered, based-on-time-tested-principles-of-organization-and-sound-logic, designed-to-teach-by-example-rather-than-precept, innovative, behavioristic, provocative, and mildly comforting reader.”

In short, it was the perfect textbook for a volatile, confounding time. (Though not, as it happened, perfect for posterity: Read On, Write On appears to have gone out of print not long after its first publication.)

I can imagine Didion forever spiking “On Becoming a Cop Hater” simply because she regretted its appearance in an anthology whose title punned on the expression “right on.” The horror! Less whimsically, I can see why the late-1970s Didion would have distanced herself from the person she had revealed when she wrote the essay—the person who had identified with the Silent Generation but also had been stretched, by her run-ins with police authority in the 1960s, to hate cops. What a psychological and political mess that era had been, so troubling and so revealing, and the evidence of her own ambivalence was lying there in the archive of all her “Points West” pieces—in the crosstalk they made. It would be harder to justify quietism and enjoy “quiet days in Malibu” if your own past voice were piercing through the sound of the waves and calling you to account.